Introduction

Myanmar is preparing for a multi-party democratic general election, to be held on 8 November 2020.1 Some count this as the country’s third multi-party election2, but some external observers count it as the second3. The current Hluttaw’s term will end on 31 January 2021. 93 political parties are running in the 2020 Election and among these, 47 are led by ethnic minorities.4 Nine political parties were rejected by the Union Election Commission (UEC)5, in accordance with the Political Parties Registration Law (published on 30 Sep 2014)6.

About the Hluttaws

The total number of seats for elected bodies is 1157, including 168 seats for the Amyotha Hluttaw (Upper House), 330 seats for the Pyithu Hluttaw (Lower House) and 659 seats for the State and Regional Hluttaw.7 The maps of constituency boundaries of three Hluttaws for the 2020 General election8, prepared by Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU), show the townships included in the respective constituencies.

Data and information about previous elections and their impact on the various Hluttaws’ seats is available here.

Voters in Myanmar

There are 37 million registered voters in Myanmar, which is 67.5% of the total population of Myanmar, or 54.8 million9 people in 2019. Five million of these are first-time voters. Registered voters from Yangon account for about 12% of total registered voters.10 These numbers do not include military personnel and their families, as the military prepares its own lists, which are not published by the UEC.11

To be eligible to vote, a person must be 18 years old on election day; be a citizen, an associated citizen, or a naturalized citizen who does not contravene the Hluttaw Election Law; and whose name must be included in the voting list of the respective constituency.12

Potential Issues

Myanmar’s previous election was held in 2015. In that year, 70% of eligible voters voted. Issues that arose in this election related to the fairness of the election process, especially about the system of proportional representation for the upper and lower houses of parliament.13 Myanmar has since held two by-elections, in 2017 and 2018. Citizen turnout for the 2017 by-election was 37%, and it grew to 42% in 2018.

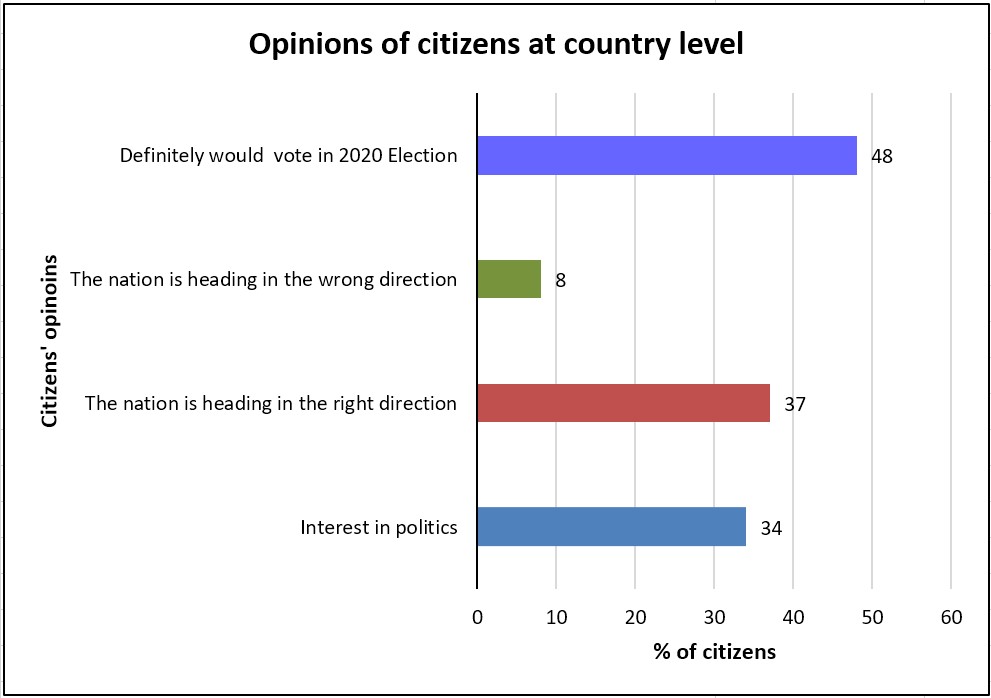

The People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE) conducted a poll in July 2019 on Myanmar citizens’ political preferences for 2020.14 They found that one third of polled citizens are interested in politics and among them, 42% are male and 27% are female. 37% of polled citizens think the nation is heading in the right direction and 8% think it is heading in the wrong direction. 48% of respondents in Myanmar indicated that they would definitely vote in the 2020 General Election; 51% of people in Yangon indicated the same. It also gives the reasons for why 52% of the population noted they might not vote: 30% are not interested, 11% have no ID, 14% are not on the voters’ list, and 8% live too far from the polling station.

Figure: Opinions of citizens on voting, current country’s direction and interest in politics. Created by ODM. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Another aspect of Myanmar society is that it holds some of the most conservative views about women in the Southeast Asia region.15 This means that women, with the exception of Aung Sang Suu Kyi, are primarily absent from public life. Most people in Myanmar hold unequal views on gender roles and womens’ rights. One 2014 Asia Foundation of 3000 people noted that the majority of respondents believed that men make better political leaders than women.16 Total of 6,969 parliamentary candidates are running in the 2020 Myanmar Election, with 1,122 women (or 16% of the total candidates) running.17 This is higher than the women’s participation rate in the 2015 election, which was 13% (800 women out of 6,039).18

Will COVID-19 impact the election?

Local transmission of COVID-19 started again in Myanmar in the middle of August, just a few weeks before the start of the election campaign period on 8 September 2020. The campaign period is scheduled for 60 days and will run to 6 November 2020 at 12am.19 The election is scheduled to go on as planned.

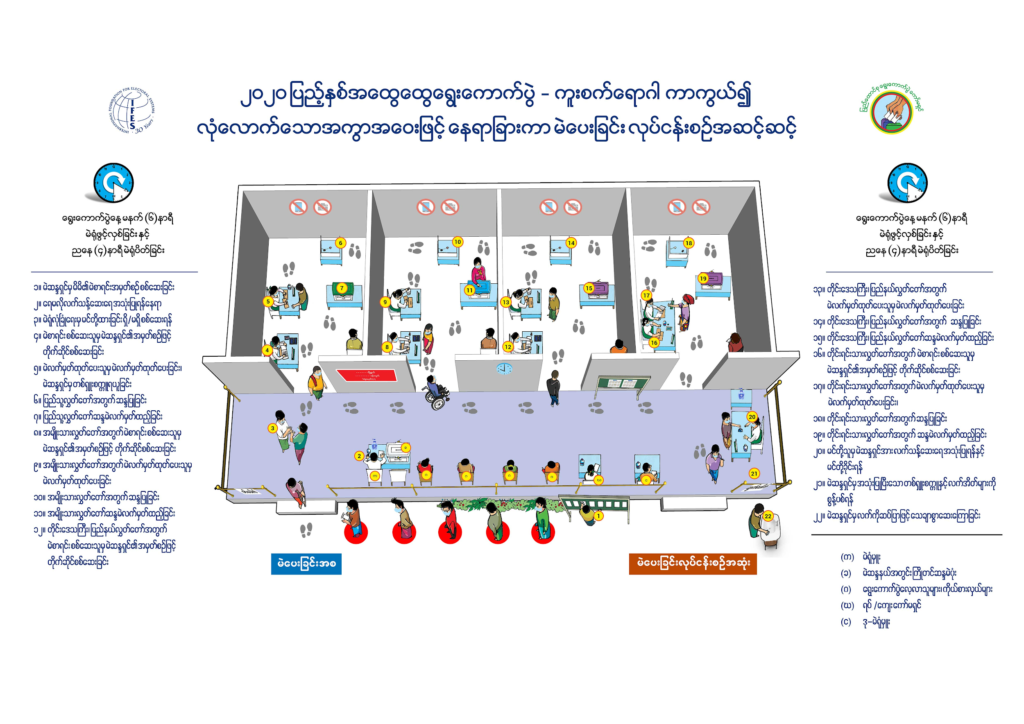

Some modifications will be made to procedure, to account for COVID-19. Government restrictions continue to apply, including stay-at-home orders in some locations.20 In these regions, election campaigns with gatherings are paused, potentially decreasing the enthusiasm of voters for the November election. Lockdown may also limit the ability of voters to go to a voting place to vote. But, online campaigns, distribution of stickers, and putting up stickers and flags are ongoing. In addition, the Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) has issued the order to hold the election campaigns with a maximum of 50 people and in line with standard election operating procedures (1): guidelines for election campaigns21 and (2): guidelines for polling station layout, station workers and voters22.

Access to news plays a vital role in elections, and COVID-19 has also increased the importance of access to information. The main source of political news in Myanmar is Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV).23 Others include newspapers and journals. Social media is also a popular news source. However, online information is limited in some townships in Rakhine and Chin State, due to a government-imposed internet shutdown since June 2019.24 The reason for this, given by the government, is for security, as fighting between the ethnic Arakan Army and Myanmar Military continues in these locations. Such information blackouts mean that people in these areas have limited access to up-to-date information about both the 2020 Election, as well as the coronavirus pandemic. The Ministry of Transport and Communication has not disclosed the duration of this internet shutdown.

One target for Sustainable Development Goal 1625 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions is to “Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements”. The internet shutdown challenges the Myanmar Government’s ability to achieve this target, despite localization of the SDGs.

What is being done?

Some parties have asked the UEC to postpone the election due to COVID-19, but the UEC has decided to continue as scheduled. The UEC has included MoHS’s Standard Operating Procedure and related health guidelines and orders in its announcement on election campaigns and gatherings (173/2020).26 Special voting procedures take into account preventing the spread of COVID-19. These procedures have been published on posters27 showing the layout of the voting booth and voting steps to assist the voters. Workers have been trained, and these procedures have already been trialed.

On 29 September 2020, a mobile application, mVoter, was launched by UEC, the Asia Foundation and International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA).28 The mVoter 2020 application gives information on candidates, political parties, voting process and other information issued by the UEC. It is intended to help voters access election information during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it has been criticized due to the way it describes the race and religion of candidates. The app uses the term “Bengali”, a term preferred by the Myanmar Government, instead of “Rohingya”, which is preferred by Rohingya themselves. It can be seen on the biodata of the candidate Dus Muhammed (also known as Aye Win) for Maungdaw Pyithu Hluttaw.29

What more can be done? What data gaps are there?

The first list of eligible voters for the 2020 Election was announced in July and August 2020. This list is based on data collected from the census, national registration cards, and in door-to-door surveys. Inaccuracies on the voter list stem from inaccuracies in these datasets, which also do not necessarily represent all people in Myanmar. These dataset issues include discrepancies in categorizations of ethnicities30, as well as errors in data collection, verification, and digitalization31. Over a million people were not enumerated on the most recent census, impacting the voter list32. Voters are instructed to identify errors in and objections based on the initially posted voter list, by using forms for each relevant issue. UEC describes the list checking process on their website and Facebook page. According to the UEC, the first voter list was checked by 6.6 million people33 which is 12% of the total population of Myanmar.

Based on these claims, the second and final edition of the eligible voter list was prepared and published on 1 October 2020. It is available at the UEC offices for 14 days.34 The list is also available via the UEC’s web and mobile application, and voters can also make corrections and objections using this application. The UEC has developed separate web applications for states and regions, as well as for Yangon itself. However, not all people in Myanmar are able to access the tools to use it: in 2019, only 59% of Myanmar citizens had a smartphone and internet access, while 15% had no access.35

UEC has posted not only election-related news and information on their Facebook page and national newspapers, but also information regarding the Hluttaw Election Law. They have drawn attention to Sections 58(d) and 59(g), concerned with the punishment on voting times and disruption of voting or election. The Ananda, a non-profit organization advocating for open government, has commented that posts of such legal information may be interpreted as a means of UEC to encourage voting.36 At the same time, the All Burma Federation of Student Unions is campaigning to boycott the upcoming elections, also called the “No Vote” campaign.37 This organization believes that the elections are undemocratic because they are held under the military-backed 2008 Constitution. On 3 November 2020, relating to the advance voting process, UEC has announced that spreading the incorrect and baseless information is in violation of Section 58 (d) of the relevant Hluttaw Election Law.38 Moreover, UEC has recently charged 2 women for voting two times and for giving a tick-marked fake seal, under the Section 59 of Hluttaw Election Law.39

The required qualifications to be an eligible voter has meant that hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people, including the Rohingya living in villages and camps, cannot vote. Additional controversy has arisen regarding the rejection of six of 12 Rohingya candidates for the 2020 election40 due to the citizenship requirement under the Election Law41. Thus the United Nation Human Rights Council has commented that the 2020 Election will not meet international standards due to the lack of fairness for Rohingya.42 On 16 October 2020, UEC has announced the areas in Kachin State, Kayin State, Bago Region, Mon State, Rakhine State and Shan State, where the election cannot be held due to the lack of the condition for free and fair election.43 Some townships where the election cannot be held, are located in the self-administered division and zones in Shan State and the below table lists these 9 townships.

Table: Townships of no-election areas in self-administered division and zones

|

No. |

Description |

State/ Region |

District |

Township |

|

1 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Hopang |

|

2 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Mongmao |

|

3 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Pangwaun (Panwai) |

|

4 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Matman (Metman) |

|

5 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Namphan (Nahpan) |

|

6 |

Wa Self-Administered Division |

Shan |

Hopang |

Pangsang (Pangkham) |

|

7 |

Kokang Self-Administered Zone |

Shan |

Laukkaing |

Konkyan |

|

8 |

Pa Laung Self-Administered Zone |

Shan |

Kyaukme |

Mantong |

|

9 |

Pa Laung Self-Administered Zone |

Shan |

Kyaukme |

Namhsan |

The list of no-election areas in Paletwa Township, Chin State was also announced by UEC on 27 Oct 2020.44 However, UEC has removed 7 village tracts in Rakhine State, and 1 ward and 2 village tracts in Shan State from the list of no-election areas on 27 October 2020, according to the report of the respective election sub-commissions and the relevant ministries.45

Voters aged 60 and above can vote in advance from 29 October to 5 November 2020 and in this advance voting process, it is expected that errors in sealing envelopes and marking ballots will occur. Thus UEC has defined the conditions in which the ballots will not be rejected.46 Election campaigns must end at 12 midnight of 6 November 2020 until the completion of elections on 8 November 2020.47 During this period, political parties, candidates and electoral representatives are not permitted to post content related to the electoral campaign on social media and other media channels.48 On the election day, all of the registered voters of all townships including the townships designated in stay-at-home programme, can vote at the respective polling stations.49

References

- 1. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcing the date for holding multi-party democratic elections for each Hluttaw. Accessed October 2020.

- 2. See, for example, The Diplomat. 2020. Myanmar’s 2020 Elections: What Does the Future Hold?. Accessed October 2020.

- 3. See, for example, Human Rights Watch. 2020. Myanmar: Election Fundamentally Flawed (Rohingya Excluded, Unequal Media Access, Arrests of Critics). Accessed October 2020.

- 4. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. List of existing political parties (93 nos.) Accessed October 2020.

- 5. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. List of rejected political parties (35 nos. from 2010 to 2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 6. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Political Parties Registration Law (Edition as of 30 Sep 2014). Accessed October 2020.

- 7. Myanmar Electoral Resource & Information Network (MERIN). 2020. 2020 General Elections: Everything you need to know. Accessed October 2020.

- 8. The Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU). 2020. Atlas of Myanmar Election Maps (2010-2018) and 2020 Constituency Boundary Maps and Shapefiles. Accessed October 2020.

- 9. Department of Population, Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Home: Myanmar Population as of 2020. Accessed October 2020.

- 10. The Interpreter, The Lowy Institute. 2020. Myanmar election: A fractured process. Accessed October 2020.

- 11. International IDEA (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) Myanmar: STEP DEMOCRACY Programme funded by the European Union. 2020. 2020 General Election in Myanmar- Fact Sheet. Accessed October 2020.

- 12. The Global New Light of Myanmar on 7 Sep 2020, Ministry of Information, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Who is eligible to vote? Who is ineligible to vote? NATIONAL 3. Accessed October 2020.

- 13. Institute for security & Development Policy. 2015. Myanmar’s 2015 General Elections: Structure, Process, and Issues. Accessed October 2020.

- 14. People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE). 2019. Citizens’ Political Preferences for 2020 (July 2019). Accessed October 2020.

- 15. Mala Htun & Francesca R. Jensenius, Springer Link: The European Journal of Development Research volume 32, pages 457–481(2020). 2020. Political Change, Women’s Rights, and Public Opinion on Gender Equality in Myanmar.

- 16. The Asia Foundation. 2014. Myanmar 2014: Civic Knowledge and Values in a Changing Society. Accessed October 2020.

- 17. News and Periodical Enterprise. 2020. With the 2020 general election (36): Scrutiny and approval of nominations of candidates. Accessed October 2020.

- 18. The Irrawaddy. 2020. More than 300 women candidates in the 2020 General Election. Accessed October 2020.

- 19. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcement of Electoral Assembly and Campaign Rights (173/2020, 6 Sep 2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 20. Ministry of Health and Sports, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. MOHS Orders for Stay-at-Home Programme. Accessed September 2020.

- 21. Ministry of Health and Sports, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Standard Operating Procedure (1) for General Elections to prevent COVID-19 spread: Guidelines for election gathering and campaign activities (7 Sep 2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 22. Ministry of Health and Sports, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Standard Operating Procedure (2) for General Elections to prevent COVID-19 spread: Guidelines for polling station layout, station staff and voters (9 Sep 2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 23. Myanma Radio and Television, Ministry of Information. 2020. Home: Myanma Radio and Television. Accessed October 2020.

- 24. Telenor Group. 2019. Network shutdown in Myanmar, 21 June 2019. Accessed October 2020.

- 25. Open Development Myanmar. 2018. Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed 23 May 2018.

- 26. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcement of Electoral Assembly and Campaign Rights (173/2020, 6 Sep 2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 27. Myanmar Electoral Resource & Information Network (MERIN). 2020. 2020 General Elections: Everything you need to know. Accessed October 2020.

- 28. The Global New Light of Myanmar on 30 Sep 2020, Ministry of Information, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. UEC Chairman launches mVoter2020 mobile app online. Accessed October 2020.

- 29. Justice for Myanmar. 2020. Calls for immediate removal of all “race” and “religion” data from the app. Accessed October 2020.

- 30. BNI Multimedia Group. 2020. Shan-Ni ethnics likely to lose their voting rights in 2020 Elections. Accessed October 2020.

- 31. The Irrawaddy. 2020. Election 2020: Myanmar Election Officials Scramble to Correct Error-Riddled Voter Lists. Accessed October 2020.

- 32. Open Development Myanmar. 2016. Population and censuses. Accessed 21 November 2016.

- 33. State Counsellor Office, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. State Counsellor discusses preparations for conducting elections during COVID period. Accessed October 2020.

- 34. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Request to the electorate to check their name on the voters’ list. Accessed October 2020.

- 35. People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE). 2019. Citizens’ Political Preferences for 2020 (July 2019). Accessed October 2020.

- 36. The Ananda. 2020. Alert! Election Ahead!. Accessed October 2020.

- 37. Myanmar Times. 2020. Parties in Myanmar slam ‘no vote’ campaign on social media. Accessed October 2020.

- 38. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcement about spreading election disinformation_UEC_3 Nov 2020. Accessed November 2020.

- 39. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcement on legal actions taken under section 59 of Hluttaw Election Law_UEC_3 Nov 2020. Accessed November 2020.

- 40. Fortify Rights. 2020. Myanmar: Prevent exclusion of Rohingya candidates from national elections. Accessed October 2020.

- 41. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Election Laws for Hluttaws (edition on 24 Dec 2019). Accessed October 2020.

- 42. The Diplomat. 2020. Myanmar election will fail to meet proper standards: UN. Accessed October 2020.

- 43. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Union Election Commission announces the areas where the election cannot be held. Accessed October 2020.

- 44. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Announcement on the list of no-election areas in Chin State_(200/2020). Accessed October 2020.

- 45. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Removal from the list of no-election areas_201/2020, 202/2020. Accessed October 2020.

- 46. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Notification for advance voters_30 Oct 2020. Accessed November 2020.

- 47. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Election campaign cessation dates_UEC (203/2020). Accessed November 2020.

- 48. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Annoပuncement on prohibition for posts on social media and other channels_UEC_3 Nov 2020. Accessed November 2020.

- 49. Union Election Commission, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. 2020. Informing the voters to be able to give their votes on election day_UEC_4 Nov 2020. Accessed November 2020.